Archaeologists use lidar and other imaging techniques to reveal details about ancient cities and civilisations, previously hidden in the thick vegetation of Mesoamerica.

When Luke Auld-Thomas, a PhD student at Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, US, found a lidar study of the area on Google, performed for environmental mapping purposes, and used archeological techniques to process the data, he found signs of an ancient city that he believes could have been home to between 30-50,000 people at its peak.

Archaeology at speed with lidar

Archaeological surveys used to be done by foot and hand, using simple hand-held tools and instruments to meticulously scour the ground and the sub-surface inch by inch. But this process was time consuming, and selective over where it looked. The Campeche-site, for example, with Auld-Thomas and colleagues have named Valeriana after a local lagoon, was just 15 minutes hike from a major road, near a current Maya settlement.

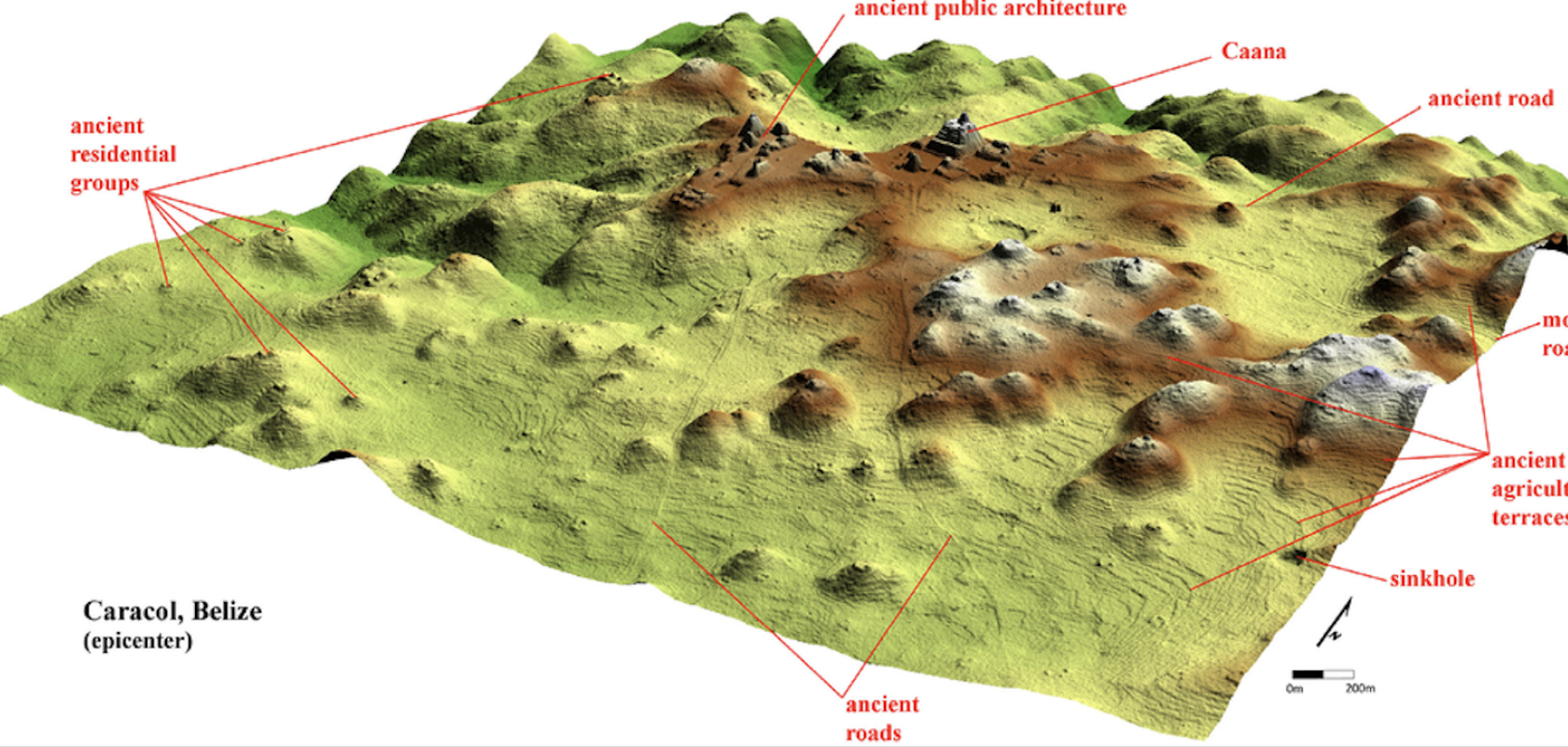

Lidar technology shoots rapid laser bursts and measures the time it takes for them to hit the ground and return. This generates a three-dimensional map with topographical markings, which reveals hidden structures and other features underneath the vegetation.

While lidar has been as an archaeological tool in the Mesoamerican region for around a decade, it has already mapped roughly ten times the area previously covered in the past century, and archaeologists are struggling to find the time to visit them all. “One of the downsides to discovering new Maya cities is that there are more than we can ever hope to study,” said Auld-Thomas.

Auld-Thomas and his colleagues have discovered as many as 6,764 buildings after surveying just three different sites in the area, so although he is keen to visit Valeriana in the future — “It’s so close to the road, how could you not?” — with so much more to study, he may not get the chance.

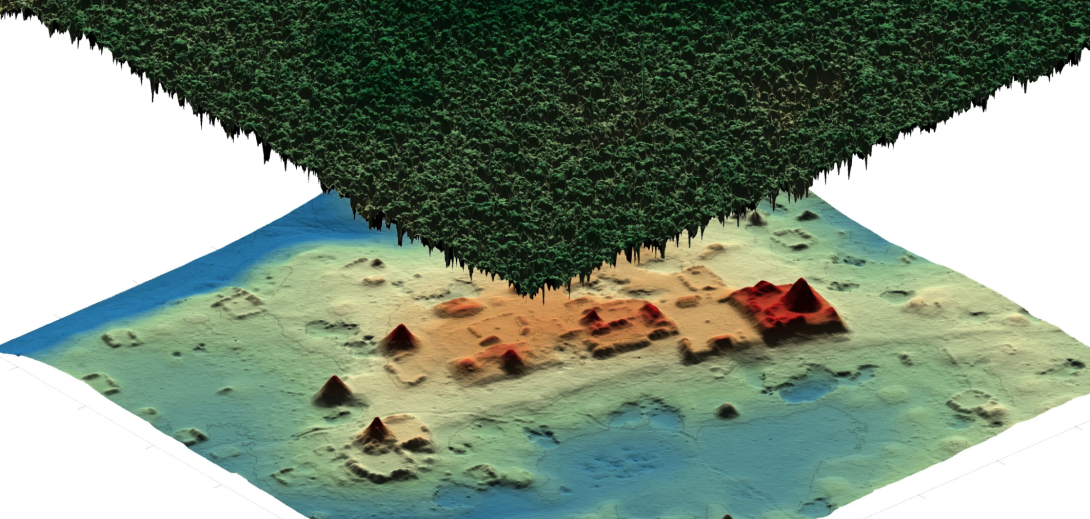

A 3D lidar model of a small portion of the Maya site of Ocomtun revealed under the dense forest canopy. (Image: University of Houston)

Other lidar finds

While lidar was first used for initial archaeological studies in the fields and ancient castle sites in Europe in the 1970s, the technique gained prominence in the next few decades due to the introduction of GPS, and has been used for many studies across north and central America.

Just last year, for example, archaeologists found another lost city they named ‘Ocomtún (translating to ‘stone column’ in Maya), after experts from the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) at the University of Houston flew a plane over sites of interest.

Researchers fly over the bay and city of Campeche. (Image: University of Houston)

Other imaging technologies used for archaeology

But lidar is only the first page of information. To get the full page of the story, archaeologists still need to visit the sites themselves. At that point, other imaging technologies can provide a more detailed picture of the past. “You can compare us to ultrasound technicians. We are the first to see the baby, but the doctor will tell you all about it and confirm the findings,” said Juan Carlos Fernandez-Diaz, co-principal investigator of NCALM.

When a team from the Universities of California and Texas used lidar technology to map El Zota, a Mesoamerican site in San Jose, Guatemala, they used lidar imaging to map unexcavated tunnels and tomb chambers on the site in minutes. Structure-from-motion (SfM) imagery was also used to create 3D digital pictures of artefacts such as an ancient pot painted with an image of a spider monkey, by stitching two dimensional photographs from multiple angles together.

“Images like the one of the spider monkey pot really help archaeologists to visualise objects in 3D without needing to physically hold them. This is also a great way to share the thrill of discovery with the public,’ said project director Thomas Garrison from the University of Southern California.

Through the combination of ground-, drone- and satellite-based lidar and other 3D imaging technologies, we can learn a lot more about these ancient civilisations, about their architecture, lifestyles and cultures, and the reasons for their ultimate demise.